Defenders don’t have to outspend or outnumber attackers—they just need to change the rules.

In this episode, RunSafe Founder & CEO Joseph M. Saunders explains how organizations can adopt an asymmetric cyber defense strategy that dramatically reduces exploitability across entire classes of vulnerabilities. Instead of reacting to every new CVE, Joe outlines how automated build-time protections can neutralize memory safety flaws, disrupt attacker workflows, and free teams from constant firefighting.

Joe and host Paul Ducklin explore why adversaries currently enjoy a resource advantage, how embedded and OT systems face unique risks, and why a shift toward Secure by Design is essential for resilience across critical infrastructure.

Watch to learn:

- How to flip attacker economics to favor defenders

- Why memory safety flaws remain the top driver of cyber risk

- Where patchless exploit prevention fits into modern security strategies

- How AI-generated code could introduce new silent vulnerabilities

- What teams can do today to build more resilient systems for tomorrow

If you’re building or protecting devices that must run safely for years—or even decades—this is a must-watch conversation.

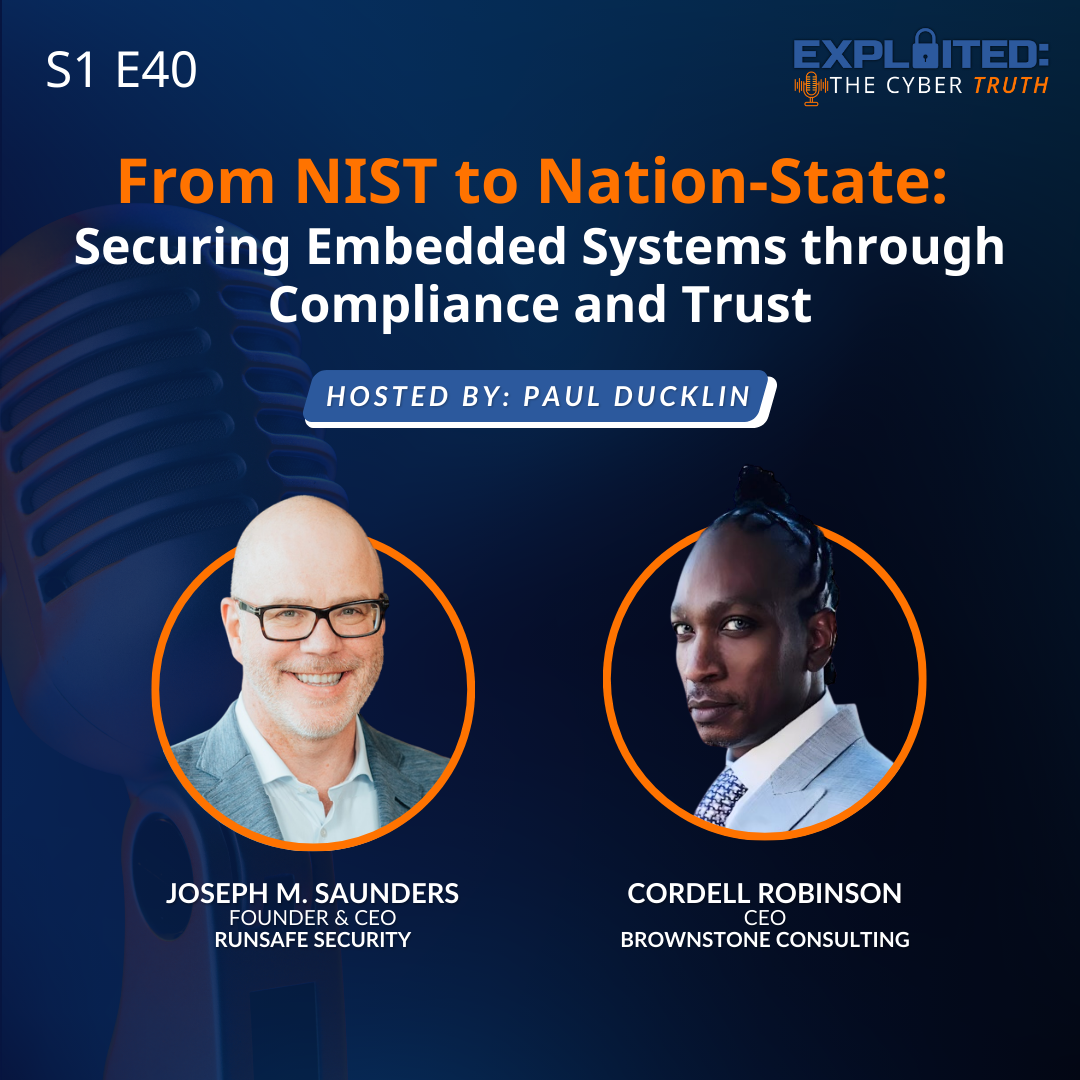

Speakers:

Paul Ducklin: Paul Ducklin is a computer scientist who has been in cybersecurity since the early days of computer viruses, always at the pointy end, variously working as a specialist programmer, malware reverse-engineer, threat researcher, public speaker, and community educator.

His special skill is explaining even the most complex technical matters in plain English, blasting through the smoke-and-mirror hype that often surrounds cybersecurity topics, and helping all of us to raise the bar collectively against cyberattackers.

Joseph M. Saunders: Joe Saunders is the founder and CEO of RunSafe Security, a pioneer in cyberhardening technology for embedded systems and industrial control systems, currently leading a team of former U.S. government cybersecurity specialists with deep knowledge of how attackers operate. With 25 years of experience in national security and cybersecurity, Joe aims to transform the field by challenging outdated assumptions and disrupting hacker economics. He has built and scaled technology for both private and public sector security needs. Joe has advised and supported multiple security companies, including Kaprica Security, Sovereign Intelligence, Distil Networks, and Analyze Corp. He founded Children’s Voice International, a non-profit aiding displaced, abandoned, and trafficked children.

Episode Transcript

Exploited: The Cyber Truth, a podcast by RunSafe Security.

[Paul] (00:06)

Welcome back everybody to this episode of Exploited: The Cyber Truth. I am Paul Ducklin and I am joined by Joe Saunders, CEO and Founder of RunSafe Security. Hello, Joe.

[Joe] (00:21)

Hey Paul, I’m ready to shake it up and duke it out. Let’s go.

[Paul] (00:25)

Before we start, it’s probably worth saying that we just happened to be recording this on 11.11, Armistice Day, or Veterans Day, as you call it in the US. So we should say, lest we forget. And when we’re thinking about things that we should not forget, and what we can do for the greater good of all, Joe, this week’s topic is a lovely one.

The Asymmetric Advantage: How Cybersecurity Can Outpace Adversaries. To read the media, some angles of cybersecurity coverage, you’d think that cyber criminals and state-sponsored attackers are light years ahead and we’re never going to catch up and we’re all doomed. But you don’t see it that way, do you?

[Joe] (01:16)

Well, I think competition with China and the U.S. actually elevates the question because if you think about China, they have an FBI director, Ray, about a year and a half ago, almost two years ago now, demonstrated that they have a 50-to-one manpower advantage in the so-called cyber warfare. And so if China has a 50-to-one advantage over the U.S., they have a massive advantage over everybody else.

And so I do think it begs the question, how do you come at the problem if someone has a 50-to-one advantage?

[Paul] (01:53)

I guess implicit in that 50-to-one advantage is not just that they have a much bigger population than the United States, they don’t have 50 times as many people, it just suggests that they’ve got more money to throw into the problem as well, and maybe more laws like, hey if you find a vulnerability you have to tell the government first and then they decide which ones get revealed. So if the playing field isn’t level, then you have to find a cool way of making the balls roll differently, don’t you?

[Joe] (02:24)

You do. And your point is valid that if it’s beyond just the manpower and it’s the other advantages, well, one thing that can help to neutralize that advantage is technology and innovation. That’s where the concept of an asymmetric approach to cyber defense comes from. How can you change the playing field? How can you shift the tectonic plates in a way that resets the playing field, resets the rules, or at least changes the dynamics between adversary and defender. That’s where there is all sorts of room for creativity and innovation, and certainly approaches to cyber defense that help shift that balance in general.

[Paul] (03:10)

Yes, it’s always worth investing in things that make bad things less likely to happen, isn’t it? A great example might be automotive safety or road safety. It’s my understanding that in the United Kingdom, if you go back 100 years to the 1920s, there were far fewer cars and far fewer people and far fewer miles driven. Despite that, there were still more road deaths then than there are now. And some of that is that drivers have got better, and driver training has got better, and licensing has got more relevant. But a lot of it is that the vehicles we drive around in are just harder to do damage with by mistake, because we’ve put effort into making them safer even if the driver is still a… that seems to me pretty strong evidence that you can make a huge difference.

[Joe] (04:10)

It can make a huge difference. When you think about an asymmetric shift in traditional cyber defense, you’re thinking about how do I patch this vulnerability to stop that attack? Well, that’s a sort of a one-to-one response, and you’re always reactive, you’re always playing defense in the sense. But how can you go on offense and create greater resilience by shifting the rules? And in your automotive example, the rule shift is not how do we improve security?

But how do we ensure safety and that safety mechanism over time has meant fewer deaths. And also from a security perspective, as we see productivity gains in autonomous driving and the like, well, the auto industry is very attuned to safety. so security in an autonomous world must equate to safety. My point is, ultimately, if you think about it as traditional defense, how am I going to patch this vulnerability, then you may not have the breakthrough idea. But if you think about it from a safety perspective or a different perspective, then you’ve got an opportunity to make a step function shift in cyber defense in general. And so I have other examples I’d be happy to go into.

[Paul] (05:24)

Why don’t you start with one of those examples right now, Joe. Just lead away, because I think it’s fascinating how much you can do if you pick a few smart things to do that affect the entire playing field, as it were, rather than, as you say, just saying, well, every time the other guy gets a body blow in, I’ll make sure I get a body blow back. Every time he hits me in the head, I’ll make sure I return a blow to the head.

Even if you win in the end, it’s going to be a bit of a Pyrrhic victory, isn’t it? You need something that kind of rewrites the rules so that it’s too hard for the other guy to continue.

[Joe] (06:03)

Certainly counterpunching is a form of deterrence. And I think that leads to a difficult situation that escalates because it may continue and maybe you fight back a little bit harder. You punch a little bit harder. Someone else wants to retaliate again to give you two examples, certainly near and dear to the founding story of RunSafe is the story around memory vulnerabilities in software. These vulnerabilities have existed since the eighties since we’ve known about vulnerabilities.

[Paul] (06:35)

Well, we just passed the anniversary of the internet worm, didn’t we? 2nd of November, how much we have learned in all those years, 37 years, Joe. It was weak passwords, misconfigured servers, and a buffer overflow. Plus ça change plus c’est la même chose.

[Joe] (06:41)

Yes. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Patching vulnerabilities has sort of been a go-to necessary step for everybody. At some point, constantly chasing patches, it’s exhausting, and you’re always one step behind the adversary and you’re reactive. And so can you change the playing field? Can you make it so even if something is not patched, you can still prevent exploitation?

Changing that mindset, and that’s what we set out to do at RunSafe. Some folks might call it patchless security, meaning even if there isn’t a patch, you can still prevent the exploitation without even knowing what the attack vector actually looks like before the vulnerability is discovered. How do you prevent a zero day from becoming a zero day? And the way we do it at RunSafe is we address the vulnerabilities in a different way. We relocate those functions uniquely in the software every time the software loads on a device out in the field. And the benefit of that is the attacker never knows exactly where that vulnerability is going to be in memory. That’s a very specific example, obviously near and dear to the RunSafe founding story of finding a different way to do cyber defense that is asymmetric.

[Paul] (08:22)

Now Joe, not claiming that this obviates the need for patches when they’re required, or that everyone else has got it wrong, are you? But what you are saying is that it’s better to be in a situation where if you can’t get a patch out, or if it’s going to take weeks, months or even years, which is much more likely in an embedded system than it is on the average Windows laptop, then you still have a fighting chance.

And that also means that you don’t need to break into a sprint every time there’s a vulnerability reported, with the result that you’re basically sprinting to finish a marathon. You’re able to pick the sprints that you need to do for the patches you absolutely cannot avoid and not spend time just always having to counterpunch.

[Joe] (09:14)

Exactly right. The patching process, if you can smooth that out and you can free up resources in a more predictable way, introduce updates in a more rational way, not in a reactive way, a more predictive proactive way, then you can focus your development efforts on new feature development as opposed to constantly reacting and chasing the next patch or the next fix or the next bug in a reactive sense. That’s where the tectonic plate shift comes from is by redefining the landscape, you’re changing the cost structure. It really becomes an economic difference as well. This asymmetric concept. It’s a very powerful thing. And let me give you one other example, which isn’t really about security, but it is about innovation and technology for 40, 50 years, maybe even longer. Moore’s law was all about doubling capacity and compute resources every 18 months. That was sustainable only for so long. At some point it’s going to taper off.

[Paul] (10:22)

Yes, you’ve run out of nanometers.

[Joe] (10:25)

You run out of nanometers. So what do you do? You’ve got to come up with something different. The compute needs and the energy needs in today’s AI environment is completely different than it was 5, 10, 15 years ago. You look at GPUs and you look at Nvidia and you look at what’s going to happen going forward with things like system on wafer, software on wafer technology. If you can find a way to combine four or eight chips on one wafer, so to speak, without those things overheating, then all of a sudden you’ve got a massive increase, a step function increase in compute resources. Those are the kinds of things, those breakthrough in technology, that I think makes those economic shifts that are interesting out there.

[Paul] (11:15)

So Joe, what do you say to those people who can be quite vocal on technological forums on social media about the real problem being, say, C and C++ and old school languages, and what we need to do is throw out the baby, the bath, and the bathwater, and rewrite absolutely everything in a memory-safe language like Rust instead. Could we do that even if we wanted to?

[Joe] (11:43)

I think you can do it in some sectors. I don’t think it’s easy to do in embedded software in certain areas across critical infrastructure. Part of the reason for that is there are compatibility issues. There’s also resource availability and know-how issues. And then of course there’s economics that work against the industry in a way, because the buyers of the technology, those that are buying these embedded devices, expect to capitalize those over 10, 15, 20, 30 years. And so they don’t necessarily just want to update software, like in a web-based environment or cloud infrastructure environment, where it might be a lot easier to apply a patch. They also don’t want to replace the capital investment that they made because they’re trying to eke out performance for many years. In that example, there’s a reason there’s an economic benefit to come up with a way to ensure your software is memory safe now, but you don’t have to go through the pain of rewriting all your software in a memory safe language, because that will prevent you from investing in new innovation and new breakthroughs by rewriting everything. You’ll be crowding out your development effort focused on solving the memory safety issue.

[Paul] (13:01)

And it wouldn’t be a very asymmetric shift either, would it? If you think, well, we’ve got an adversary who’s got 50 times as many people on the attack job as we have, and they got 50 times as much money. What are we going to do about it? A solution that says, well, why don’t we just stop doing what we’re doing, produce no new software, no patches for a few years, and spend 50 times as much money and start again? That’s a little bit of a fool’s errand, isn’t it?

[Joe] (13:30)

Yeah, it’s almost the opposite. It’s almost the opposite step function. There’d be a step function backwards for a period of time in order to get the benefits. So ideally you can have your cake and eat it too. Have memory safety achieved today without rewriting all your code so that you have resilience in the investments that you’ve made all the while freeing up resources to do new development in areas you want to, not just rewriting legacy code to replace it in general.

[Paul] (14:05)

And Joe, what would you say to people who note that attacks against systems like iOS or Mac OS and Windows, let’s be fair, memory-based attacks are now much, much more expensive and much more difficult. In the words, has been a somewhat asymmetric shift thanks to memory protections that have been put in like ASLR address space layer randomization, stack protection, control flow guard, all of that stuff that works well on desktop and server scale systems, doesn’t it?

Because you can build a bigger operating system and a bigger cocoon in it. But with embedded devices, it’s more like saying, well, we can’t wrap the whole car in a million airbags because it still has to get down these tiny lanes. And you’re stuck with those tiny lanes in the embedded market, aren’t you? A) Because the devices are embedded and they’re supposed to last for decades, because there are zillions of them and C) Because they’ve been tested and proved to work correctly from a safety and a timing and a performance regulatory point of view as they were. New software might be more secure from a vulnerability point of view, but it won’t necessarily meet the safety requirements that that software was approved for.

[Joe] (15:29)

Yeah. And we’re operating in highly constrained environments where the compute resources might be restricted as well. Safety standards are certainly key aspects. You have to invest in getting safety certified in general, and that can be a lengthy laborious process. You have to demonstrate deterministically that everything will still operate the way you expect. And so certification is an investment on the product manufacturer side to ensure that safety, but also the hardware that’s already been invested in may come with low power, low compute resources. And you can’t just rewrite that in new software and expect that you’re going to be able to meet all the requirements that are on there.

You have performance issues, you have hardware constraints, you have economic constraints, and you have policy and regulatory constraints around safety certifications that all make rewriting a bigger task than strictly just wiping things out. And if you think of the environment on laptops, as those become more and more powerful, you can afford more and more compute resources going towards managing memory and managing exploit prevention in general. And you can’t necessarily do that in these highly constrained environments in critical infrastructure, say in the energy grid or in a data center where this stuff has to operate 24 seven or the data processing just won’t happen.

[Paul] (16:58)

Because for a lot of these devices, although I guess technically they have an operating system layer, it’s not like Mac OS or Windows, it? Where you have the operating system, which is this multi-gigabytes worth of stuff with a huge number of libraries on top of which you install apps. You want to have exactly one app that performs exactly one function in an exact and repeatable way.

So the software and the operating system are kind of one thing, aren’t they? So you can’t just wait until the operating system vendor says, oh, we’ve added all this new extra stuff. Oh, and we can sell you some cybersecurity tools, EDR stuff that you can add in as well. You have to, if you like, go back not exactly to basics, but literally to fundamentals so that the entire system, the entire firmware you deliver runs the same code. So you don’t get to change the code, but you get to change its exploitability in a way that essentially ruins the determinism of an attack without affecting the determinism of its real-time behavior.

[Joe] (18:09)

Yeah. And I like to say functionally identical, but logically unique. Right. And what I mean by that is from the attacker’s perspective, it looks different, even though functionally everything behaves the exact same way as you would expect. And that’s the premise behind relocating where functions load into memory at load time so that the system still operates. But from the attacker’s perspective, they can no longer find the vulnerability itself because it’s moved from the last time they’ve seen it.

[Paul] (18:39)

So Joe, what other threats do you see affecting particularly the embedded marketplace, where we can effectively counterpunch without landing one blow at a time in exact lockstep with our adversaries, but by building things that are more secure from the start? What changes do we need, both technically and almost socially from a DevOps point of view, to be able to build software that is sufficiently similar that it still passes all its regulatory checks, but sufficiently different that it’s no longer as easy for an attacker to break into.

[Joe] (19:21)

Well, I think you hit on the notion of Secure by Design. If you think about having highly reproducible builds that allow you to add in security as you’re compiling software, as opposed to trying to defend the network and prevent people from getting in, it’s a much more efficient process to incorporate security into your software development process in the first place, adding in security protections there, identifying and analyzing the vulnerabilities that build time. So you have a chance to understand what forms of mitigation are needed. You also can analyze those vulnerabilities, how they shift over time. But I do want to offer maybe a cautionary tale as well, which is there are movements, of course, where gen AI may start to produce some code. And I do think that could be an asymmetric shift in software development. And certainly people get great productivity gains out of the software development process. But let’s think about this for a second. There are plenty of open source software components that would work in these embedded systems quite nicely. And so we should focus the generative AI development efforts, writing new code in those areas where new code is needed. We shouldn’t necessarily try to rewrite existing open source components using AI. That’s, it almost feels like a waste of time, and sure, maybe you could get some performance gains here and there, or you might want to have something that’s a little different than what everyone else is doing.

But in the end, one of my fears in this whole equation is if a generative AI application is writing code and it rewrites an open source component so it’s a near lookalike, but it’s not the same code base, it becomes very hard to identify vulnerabilities that someone else might see in the true open source component that also exists in the near look-alike open source component that was written in generative AI. And so you lose the effect of sharing information about vulnerabilities and disclosures about vulnerabilities and information about known exploits. And someone might have a near look-alike version of that, have no idea it’s the same thing as an open source component. And it still may have its own memory-based vulnerability, let’s say. And so that system’s exposed without the network effect of sharing vulnerabilities across open source systems in general.

So I think it cuts both ways. Technology could lead to productivity gains, but could lead to some new security exposure and enable vulnerabilities that are hard to detect. And as a result of not getting the benefit from the disclosures through, say, the CVE program that hopes to share with everybody what the underlying vulnerabilities are in certain code, in certain open source software, it could put these systems at risk even further. But in that case, I do think taking this asymmetric shift in cyber defense also helps. It can prevent exploitation even on that AI-written code, even when we don’t know that the vulnerability exists in that code in the first place.

[Paul] (22:41)

So Joe, if we look to the future, what do you think are the biggest challenges and opportunities? Not just for cybersecurity in general, but more specifically in the OT arena. To do things that with hindsight we wished we’d done 10 or 15 years ago, but we didn’t. And where it’s not quite as easy to fix the sins of the past as it is, as you like to say, with a web app. Where you can quite literally fix it between one person visiting the website and the next visitor arriving.

[Joe] (23:16)

Yeah, I think some of the challenges and some of the opportunities kind of center around exploitability and knowing where there is exposure, where the vulnerabilities exist, and whether they’re exploitable. If we can focus our attention in the areas where things are no longer exploitable and take an asymmetric shift and take off a majority of the vulnerabilities and make them not exploitable. That means we can focus development in other areas, and that’s a tricky thing. For example, in the medical device arena, part of the whole vulnerability management area is to show whether it’s code quality or exploitability itself, looking at those items and demonstrating that things are no longer exploitable is really kind of the standard in order to ship software. I think the opportunity is to look for ways to prevent exploitation in an asymmetric way so that we can focus our development areas in other ways.

[Paul] (24:15)

And it sounds as though things like the Cyber Resilience Act, the CRA, in the European Union, even though it feels like quite a challenge to many people, could have a very positive effect because it’s sort of saying that if you make software and you sell it, then you have to take the liability for what you’ve built and therefore it makes economic as well as ethical and social sense to get it right in the first place.

In other words, it’s a little bit of a stick rather than just a carrot that will help get everybody moving, even those who may have been a bit reluctant so far. Would you agree with that?

[Joe] (24:56)

I would. And I think if you sort of look at the Cyber Resilience Act as a blessing, if you see it as kind of an opportunity to open the way you think about resilience and cybersecurity and look at it as an opportunity to improve your overall processes, to include your software development practices and incorporate security in from the get-go, it’s going to lead to better code quality in the end. So my point is things like the Cyber Resilience Act could be that trigger to help you transform how you go about your software development process that becomes the asymmetric shift in cyber defense by redoing your approach to security in the first place, building security in as you go forward. And so what that means is for new products, you can start to demonstrate these best practices and shift the landscape yourself and change your support cost going forward.

[Paul] (25:53)

Sure, I think that’s an excellent way to finish because it turns something that I know at least some people see, like GDPR when it came out, as just this expense that they’re going to have to go through because some regulatory body said so. But actually, if you see it as something that can help you build better products that more people will want to buy and that will last longer, that’s great for all of us. So Joe, thank you so much for your passion and your insight in this fascinating topic. That is a wrap for this episode of Exploited: The Cyber Truth. Thanks to everybody who tuned in and listened. If you find this podcast insightful, please don’t forget to subscribe so you know when each new episode drops. Please like and share us on social media as well.

That means a lot to us. And don’t forget to recommend us to everybody in your team so they too can benefit from Joe’s wisdom and insight. Once again, thanks for listening, everybody. And remember, stay ahead of the threat. See you next time.